Investigating pottery production and exchange patterns at Ayia Irini, Kea

In January, I enjoyed an all-too-short visit at the Fitch Laboratory to consult the comparative collection of ceramic thin sections, mostly from the Bronze Age Cyclades. My visit was part of an ongoing project focused on the study of pottery from Ayia Irini, on Kea. John L. Caskey excavated Ayia Irini during the 1960s and 70s. He discovered a town that was inhabited on-and-off from the Final Neolithic into the Late Bronze Age. Much of the pottery I have been studying is from Area B, which contained well-stratified deposits that date to the mid-Early Bronze Age through to the mid-Late Bronze Age (Early Cycladic II to Late Cycladic II, Periods III–VII in the parlance of the site). The deposits from Area B were methodically recorded and initially studied for publication by Aliki Bikaki, who worked with Caskey at both Lerna and Ayia Irini. Bikaki was an excellent excavator and interpreter of archaeological deposits. Her clear records—combined with the relatively straightforward deposition history of the area—have enabled a detailed analysis of changes in the ceramic assemblage through time.

Deposits in Area B span, something like, 1000 years. Accordingly, the assemblage has provided an opportunity to examine how local pottery production practices were (and were not) impacted by major social and cultural shifts in the Aegean, including the so-called Minoanization phenomenon of the later Middle and early Late Bronze Age, during which Cycladic communities adopted and adapted many Cretan ways of doing things. In addition, since Ayia Irini was a major exchange hub throughout most of its history, the assemblage is rich in imported pottery, which can provide insight into how Keian exchange networks may have changed over time.

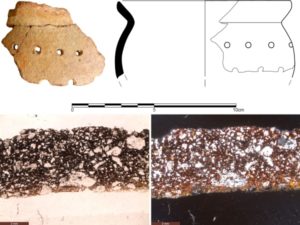

Local Minoanizing incense burner from a Late Cycladic II destruction deposit and Plane and Cross-Polar views of a sample from this vessel, typical of local products. Drawing by Aliki Bikaki; photo by the author. I am grateful to Lorene Sterner of the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology for assistance with these images.

In order to clarify how pottery production and importation patterns changed through time, I completed macroscopic and petrographic analyses of the ceramics. As part of my visit to Athens, I was able to compare many of my petrographic groups with samples in the Fitch’s reference collection. This process allowed me to verify parallels that I had found in publications, as well as to locate good comparable groups in other assemblages. Of course, consultation and conversation with the other researchers at the Fitch also provided new insights on the study, and I am grateful to everyone there for helping to make my visit very productive.

There are a couple of big takeaways from my analyses at Ayia Irini. First, the imports present a sometimes bewildering diversity of fabrics. A variety of production centres seemed to be represented, from different parts of the Cyclades, several locations in central and southern mainland Greece, as well as multiple centres in Crete and possibly the eastern Aegean as well. The fabrics also are being analysed by means of WD-XRF at the Fitch, which should help clarify the range of sources for imported pottery further. Second, local fabrics were somewhat variable, but from Period III to VII many samples show significant similarities in raw materials, processing, and firing. These technical overlaps are especially notable during the Middle and Late Bronze Age phases, before and during subsequent phases in the “Minoanization” of the town, even as the use of the potter’s wheel became common and local potters embraced new fashions in ceramic shapes and decorative modes. This evidence suggests that despite these changes in output, local potters were part of a community of practice that, by the mid-Late Bronze Age, embraced very long-lived traditions in the practical methods of making pottery.

Natalie Abell

Assistant Professor of Mediterranean Archaeology

Department of Classical Studies, University of Michigan